© Successió Miró, 2018

Moneo building

L'edifici Moneo, seu actual de la Miró Mallorca Fundació, es va inaugurar el 1992. Projectat per l'arquitecte Rafael Moneo és el resultat de la donació de Pilar Juncosa, vídua de Miró, a la Ciutat de Palma.

-

Exhibition space

- Space Estrella

- Space Cúbic

- Space Zero

-

Dates

- 17 February 2018 — 5 May 2019

-

Inauguration

- 17 February 2018

- 12:00

Miró, a wild spirit

This exhibition of Joan Miró arrives in Mallorca after travelling to Seoul, Bologna and Turin and it offers a series of keys to the artist’s inner spirit and way of thinking. No real insight can be gained without mentioning his strong attachment to his roots and to his identity, factors which had a very direct impact on his work.

Joan Miró to Georges Raillard in Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves. Entretiens avec Georges Raillard, Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1977.“Wildness is the flip side to my character—I’m well aware. Naturally, when I’m with people, I can’t be brutal in speaking and I put on, one might say, a kind of mask.”

Miró had deep-rooted ties to two places: Mont-roig and Mallorca, where he could live and work in privacy, immersed in unspoilt natural surroundings. Through the exhibition we will explore the roots of Miró’s work: primitive culture and popular art, Romanesque frescoes, Antoni Gaudí’s architecture, poetry, and his subsequent approach to American Abstract Expressionism and Oriental art. Lastly, we will discover his creative fecundity through his plastic imagination, his singular use of imagery and the variety of techniques and materials, all of which bear witness to the insatiable desire for renewal and innovation that characterized his final stage in Mallorca (1956-1983). This is a moment when he turns the gaze to his beginnings, to the landscapes and horizons of his first years. At the same time he reaches the maximum simplicity in the predominance of the empty space and closes the creative cycle with the return to the same roots that had marked the starting point.

The exhibition “Miró, a wild spirit”, narrated in the first person, is based on all the above concepts, together with Joan Miró’s conception of his work as a kind of inner monologue and, at the same time, a dialogue with the public. It is divided into four main areas of a separate and yet complementary nature. The exhibition contains works produced in Mallorca during his most dynamic mature stage as an artist —the most innovative and “wild” and yet lesser-known period—, which defines the collection of Fundació Miró Mallorca.

Roots

Joan Miró to Camilo José Cela in "La llamada de la tierra. (Acta de un monólogo de J.M.)", Papeles de Son Armadans, year II, volume VII, issue no. 21, Madrid-Palma (December 1957).“It is important to be in close contact with the land, to listen to the call of the land...”

The key to the authenticity of Joan Miró’s work is its ties with tradition and with the landscape in keeping with his belief that close contact with the land is needed in order to make a universal impression. The artist felt a deep-rooted sense of attachment to Mallorca. The island became his refuge and his home, allowing him to work in privacy, immersed in silence in primitive natural surroundings.

Miró was strongly attracted to certain past forms of artistic expression because he recognized them as being imbued with the same timeless spirit which his shapes aspired to achieve. Cave paintings are fundamental in understanding the roots of Miró’s work. Just as prehistoric man left traces of his existence on cave walls, handprints also have a profound significance for Miró. In his final years as an artist, producing work that was freer and more dynamic than ever, he even came to apply the paint directly with his fingers.

During his childhood in Barcelona, Joan Miró was able to see Romanesque frescoes and they provided an endless source of imagery for him. In their extreme flatness and pictorial sparsity, they offered a wide variety of formal solutions, including elements that would become characteristic features of his own vocabulary of signs, like eyes or stars.

Antonio Gaudí was another important reference in the artist’s work. The fragmentation of images and juxtaposition of colours, in the style of the trencadís or tile shard mosaics used by Gaudí to decorate his architecture, is clearly evident in Miró’s work, particularly in the geometries and kaleidoscopic colours of the Gaudí Series. An affinity for organic shapes, interest in collaborating with craftsmen, and constant desire to investigate and evolve are other common denominators shared by both men.

Inspiration

Joan Miró to Yvon Taillandier in “Je travaille comme un jardinier…”, XXe siècle, no 1, Paris 1959.“The atmosphere that lends itself to the mental tension is something that I find in poetry, music, architecture, in my daily walks, in certain noises.”

In addition to music, poetry was one of those pure forms of spiritual expression much admired by Miró throughout his whole life and used to help attain that sudden moment of inspiration. In his attempt to go beyond the boundaries of painting, poetry allowed him to break the established limits of plastic expression. Both disciplines share that magic instant when an idea is transferred to the support, with no distinction between words and images, between poetry and painting.

Following his first visit to the United States in 1947 and successive other trips, a progressive evolution could be seen in Joan Miró’s work. The ‘stripping back’ or simplification process was taken to extremes, with a change in the size of his paintings, his physical transposition to the canvas on the floor, the application of paint by plastering it on or using dripping techniques, explosions and diluted colours, the forcefulness of his brushstrokes, and his overwhelming brutality and primitivism, evoking the gestural expression and chromatic abstraction of young North American artists.

During his final creative period, Miró’s work underwent a renewal through direct contact with typically Oriental thinking and forms of expression, following the emotional and visual impact of his first trip to Japan in 1966. In this distant culture, the artist recognized what he had been constantly trying to convey through his paintings, as well as being influenced by the gestural quality of the brushstrokes, the combination of painting and poetry, the force of the signs, and the creator’s ritual preparation before tackling a work. It was thanks to his contact with the East that the formal relationship between filled and empty spaces and lines and black masses ended up prevailing in his compositions, evoking the spiritual tension and silence that Miró so cherished.

Oli damunt tela

Vocabulary

Joan Miró to Roland Penrose in Theatre of Dreams, a film directed by Robert Lough and shot in the Sert studio in 1978.“The ‘femme’ continues to be a ‘woman’, as is the case of the ‘oiseau’ or ‘étoile’, but the visual conception of the woman changes all the time, and the bird too–it is always different. It is very restricted: ‘femme-oiseau-étoile-lune-personnage’, etc., but each time it is different.”

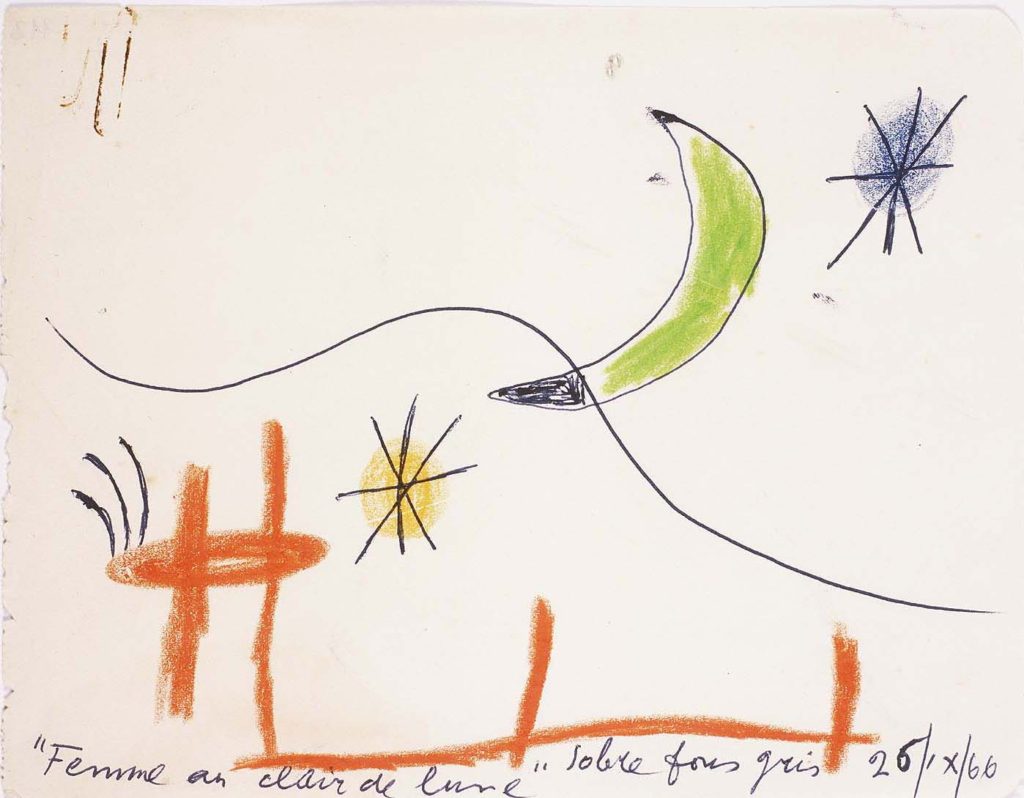

Miró’s use of images was reduced to a series of motifs that recurred throughout his work. Taken from nature and observation of everyday things, they included women, birds, stars and personages. Although the artist worked on just a few themes, when they were transformed into images, they took a wide variety of forms and visual conceptions, giving rise to a visual repertoire in a constant state of change. His paintings evolved from précieux-style portrayals to the most schematic, simplified representations.

For Miró, the image of a bird was based on his own concept of an empty space and it could even be reduced to a mere brushstroke indicative of a bird having taken flight. He tackled themes ranging from the cosmos and the sky’s stars and heavenly bodies to insects and nature’s most insignificant little details, in addition to the land and sky: the two highpoints of Miró’s cosmology.

What reigns supreme in his imagery, however, is the female image; a theme that pervades all his work, tackled from numerous different perspectives. The female sex not only symbolizes eroticism but also the maternal womb, primal instinct and the origin of all universes, thus tying in with his constellations and all the other creatures from his imagination.

All these figures offer an insight into his highly complex inner universe and his inner struggle to reconcile these contradictions with the reality of the background context. His female figures, birds and stars pave the way for a new pictorial vocabulary and universal language.

Metamorphosis

Joan Miró to Yvon Taillandier in “Je travaille comme un jardinier…”, XXe siècle, no 1, Paris 1959.“My desire is to attend a maximum intensity with a minimum of means. That is why my painting has gradually become more spare.”

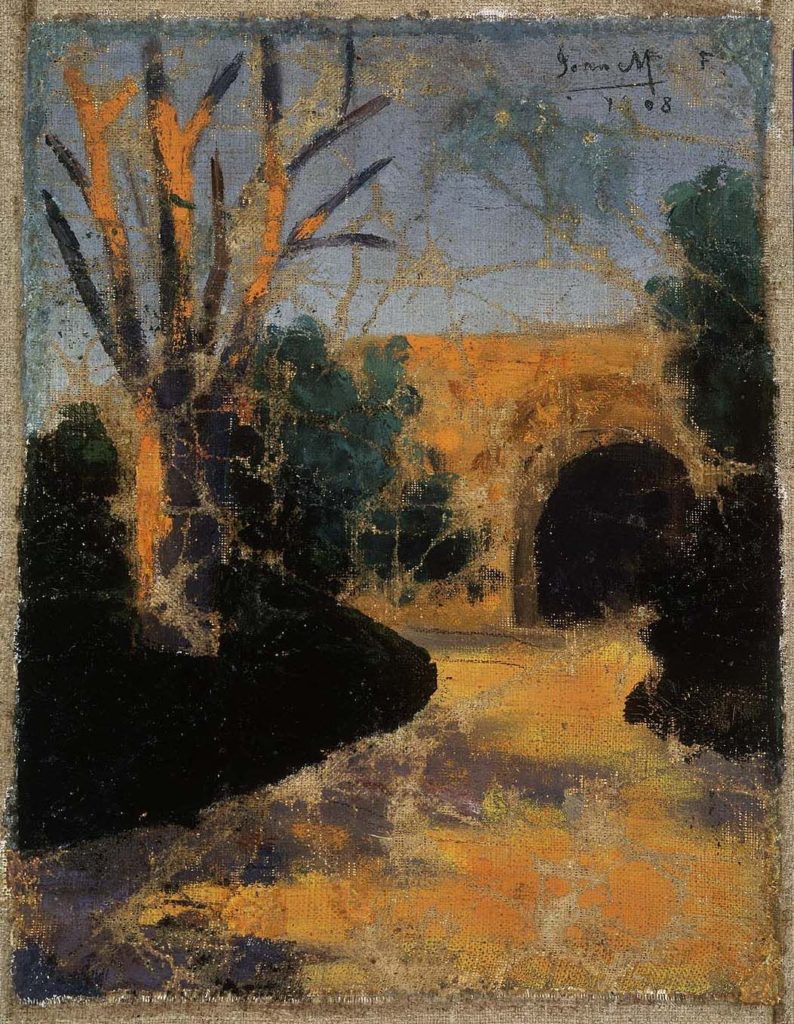

In 1956, Miró settled in Mallorca where he was finally able to have the large studio that he so craved. However, the new studio made such an impact on him that, for a while, he was unable to tackle any new paintings, and he embarked on a review of his former work, leading to a radical renewal of his artistic language.

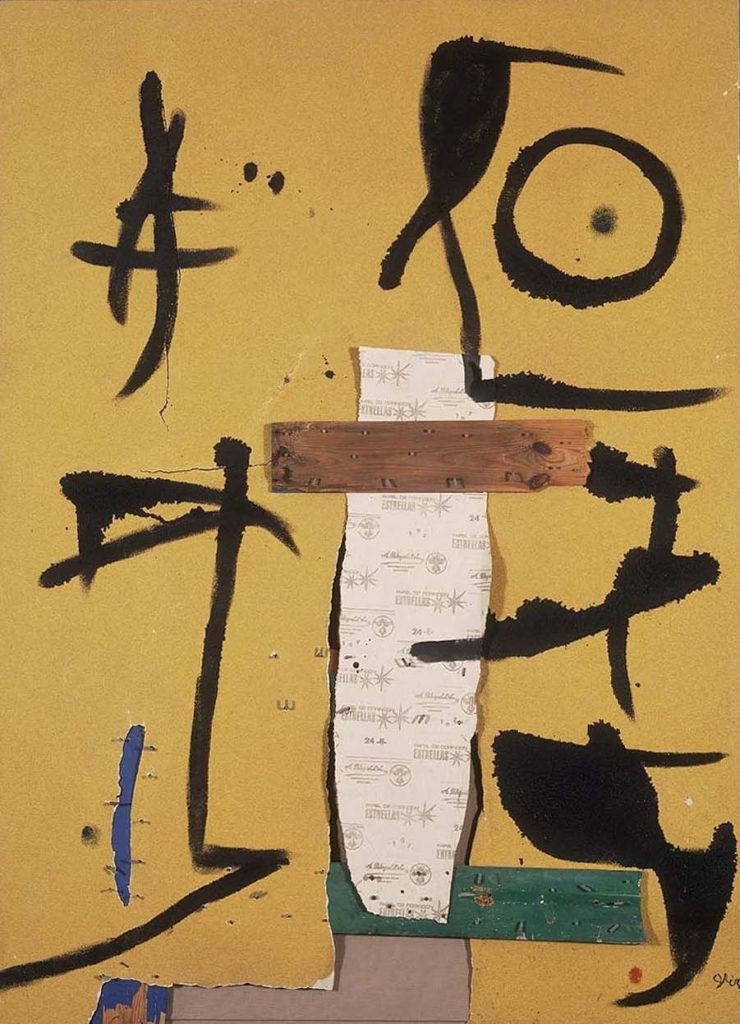

When he returned to painting, a non-conformist, rebellious, transgressive Miró was revealed who continued to look into the future at everything that was yet to be done, always wishing to go one step further even though he was now an acclaimed figure in the art world. New forms of expression were added to his traditional imagery, with the emphasis on gesture and materials, unusual supports, the use of chance or deliberate accidents, explosions of colour in contrast with a sole use of black, and experimentation with different types of media or techniques. Once and for all, Miró’s wild spirit had been let loose.

However, this major shift would lead to a cleansing process and a return to the landscapes of his childhood, to the horizons of his student years with Modest Urgell, a painter and landscape teacher at Barcelona’s Llotja School of Art & Design, and to the emptiness and silences of his years of inner exile, because acts of gut instinct were always followed by long reflections, thus bringing the circle full close with the release of the most primitive radical Miró.